The Brain’s Internal GPS Has a Design Flaw

Imagine your car showing an incorrect number of miles or kilometres travelled. You were told to turn left after 2 miles, do you turn left here? or not? You can imagine that problem applied to walking or running in poor visibility. Scientists now understand the importance of visual cues on distance perception.

A new study in Current Biology suggests that a similar kind of mileage clock exists in the brain, and the shape and features of our environment can fool it. Scientists have found that specialised brain cells responsible for navigation, known as grid cells, can become distorted in irregularly shaped spaces, leading to a significant loss in the ability to judge distance accurately.

The discovery involved experiments first with rats and then humans, offering a deep insight into how the brain’s internal navigation system works and why it can sometimes fail. The findings confirm that these cells’ precise, geometric firing patterns are essential for path integration—the brain’s built-in ability to track our position and movement without external cues.

The Mind Maze

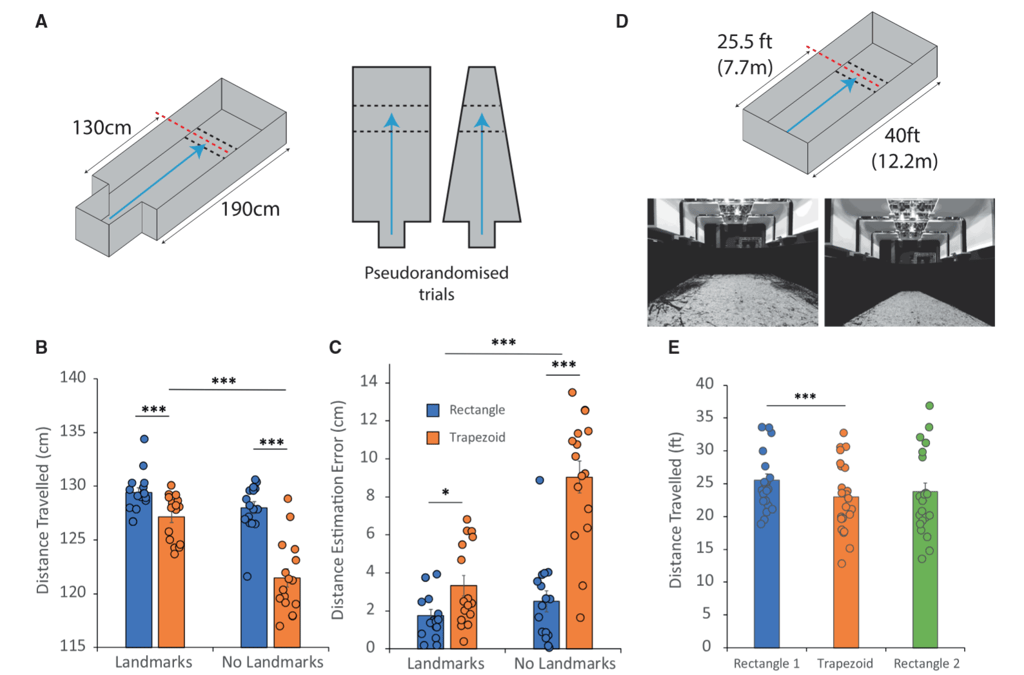

To uncover the mechanism behind this phenomenon, researchers from the University of St Andrews and University College London designed an experiment for rats that could be repeated with humans.

First, they trained a group of rats to run a specific distance in a standard box to find a reward. The rats quickly learned the task, demonstrating an impressive sense of distance by stopping after running the correct distance.

Next, the shape of the box was changed to narrow at one end, making it trapezoidal. The rats’ performance plummeted with the new shape to the extent that they consistently overestimated the distance they had run, as shown by them stopping short of the point where the reward would be expected to be issued. The human version of the same experiment used a scaled-up arena and produced identical results: human participants also stopped short in the trapezoidal arena.

Referring to this known behaviour, the scientists checked the “Grid Cells” activity in the rats’ brains while performing the task in each type of box. Grid cells are located in a region of the brain called the medial entorhinal cortex; they fire in a structured, symmetrical, and hexagonal pattern as the rat (any animal) moves through an environment. Thus, they act like a neural coordinate system.

A comparison of the recordings revealed a correlation: when the rats were in the rectangle, their grid cells fired with perfect hexagonal symmetry. But this pattern became “distorted” and less regular in the trapezoid.

“When the grid cell pattern is distorted, the brain’s ability to estimate distance is also impaired,” explains lead researcher Dr James A. Ainge. “It’s like having a faulty internal GPS. The more the grid is out of alignment, the greater the error in judging how far you’ve gone.”

The external landmarks were removed to reinforce the findings further, and the rats’ distance overestimation in the trapezoid became even more pronounced. The suggestion then becomes that while external cues can help distance perception, the brain’s internal geometric map is the primary driver of accurate distance perception.

A Map of Experience

the perception of our surroundings is impaired, such as when walking in the dark or in misty conditions.

The study also found that when the rats were returned to the rectangular box, the distortion effect remained -at least for a while. This suggests that the brain’s internal map is altered by experience, and the effects of a “polarised” environment can linger. “The brain is incredibly plastic, and this shows that its fundamental spatial representations are not fixed but are instead impacted by our recent experiences,” Dr Ainge added.

The implications of this research extend beyond laboratory animals and humans in man-made arenas. The findings could shed light on conditions like Alzheimer’s, which show links to navigational impairment. Perhaps also, when we are out in the wilds, these findings show that our perceptions of distance will be overestimated when the perception of our surroundings is impaired, such as when walking in the dark or in misty conditions.

Source:

Duncan et al., Grid cell distortion is associated with increased distance estimation error in polarised environments, Current Biology (2025), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2025.08.011 (also in cell.com)